The Radiated Tortoise Crisis: Developing a Plan of Action

by Rick Hudson

TSA and The Orianne Society are launching a partnership to develop strategies for saving this iconic symbol of Madagascar’s southern spiny forest.

We arrive in Madagascar around midnight on March 15 and by the time we get our bags and to the hotel it’s early morning on March 16. I am traveling with Christina Castellano, the newly appointed Director of Turtle Conservation Programs for The Orianne Society. She has a long-standing interest in Madagascar and intends to develop a comprehensive science-based program aimed at monitoring key populations of both radiated and spider tortoises. We are met at the airport by Herilala Randriamahazo, TSA’s Director of Tortoise Conservation in Madagascar. It has been exactly one year since I was last here and reported on the developing crisis with radiated tortoises in the south and the need for urgent conservation action. Together, Christina and I hope to determine how to best approach this problem, and to identify key populations that can still be protected. There is a sense of urgency to this mission because it appears that the situation may have finally reached the tipping point. After holding their own despite years of being harvested for food, the beautiful Radiated tortoise may be on its final legs. Our challenge is to determine a strategy that will at least preserve some healthy populations, and that solution will likely lie at the local community level. Southern Madagascar is a vast rural region where there is little capacity for enforcement of tortoise poaching activity. Enforcement is constrained by a poor communications network, and lack of transportation by officials, and lack of knowledge of the laws.

Day 1, March 16: We have lunch with Richard Lewis and staff from the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust to discuss ploughshare tortoise issues. Then we move on to the Conservation International office to discuss their grant to the TSA for Radiated tortoise projects in the south. Finally, it’s back to the hotel for a meeting with Ryan Walker (Nautilus Ecology) who has just returned from a month in the south, doing field surveys of the southern spider tortoise, Pyxis a. oblonga. Ryan and his team worked east from Cap St Marie to document the diminishing extent of the range of this tortoise, while concurrently studying the dramatically shrinking range of the radiated tortoise. Ryan admitted that he has not fully appreciated the extent of the crisis until he began looking at populations in the east, closer to Ft. Dauphin, a major center of tortoise consumption. He describes the work of well organized bands of poachers who are dropped off in an area and then very efficiently clean out the tortoises. In Ryan’s words, we are witnessing the “systematic extermination of the radiated tortoise across its range” and he predicts that soon we could find ourselves trying to protect small populations of tortoises such as we are currently forced to do in the northwest with ploughshare tortoises. He believes that our prediction last year of 20 years to extinction may be a “bit generous.”

Day 2, March 17: We are up early for a 7 a.m. flight to Ft Dauphin where we are met by our driver Henri. We head east to reach Ambovombe, capital of the Antandroy region, for the night. We are joined by Sylvain Mahazotahy, who is from the south and will prove to be indispensible over the next 10 days in communicating and negotiating with rural villagers. He is one of them, understands their customs and unique dialects, and has been conducting social surveys for us to determine why some villages have such strong tortoise protection traditions (fady) while others do not. Fortunately, the rains have stopped and the roads are dry, but in horrendous condition with massive ruts, ditches and whole sections washed away by a recent cyclone. The road bears testament to the epic battles that have occurred over the past month, between man, machine and thick mud.

Day 3, March 18: Our goal is to reach Lavanono, an hour past Cap St Marie, where we will be based for a few days. Along the way we stop in Tsiombe, a well-known tortoise consuming center, and begin asking locals if there are dump sites for tortoise shells. We are led to several sites, one in particular that is loaded with the remains of freshly killed tortoises; other sites are much older and the remains are reduced to piles of bones and scutes.

In Tsiombe there is little attempt to conceal the illegal practice of selling and eating tortoises. In fact, we manage to lure in one such seller who meets us at a restaurant and brings a pot of tortoise meat for us to buy. 2000 Ariary - the equivalent of 1 US dollar - will buy 1 kg of tortoise meat, about ¬Ω of an adult. It is hard to fathom that we are witnessing the extermination of this beautiful tortoise for about $2 per animal.

We press on and reach the village of Antsakoamasy that lies just outside the Special Reserve of Cap St Marie. Last year, we identified this village as having a strong protective attitude toward the radiated tortoise. Over the past year Herilala has been working to build a relationship between the village and the TSA. We plan to “seal the deal” with a traditional zebu festival on March 25 and we will stop and discuss plans with the village elders later in the day.

Along the way, we pass thru another small village and stop to photo a tortoise in the road. As we are pulling away, we hear shouts from children of “Don’t take our tortoises.” This is the protective attitude we are looking for, so we get out and visit with the village leaders about what fosters this attitude.

We reach Lavanono just after dark, finding a nice Dumeril’s boa in the road before we descend into the canyon where the village is found. Like Cap St Marie (CSM), Lavonono supports a robust population of radiated tortoises, protected by its isolation from the main road and limited access by poachers. The local village also provides a strong sense of protection for the tortoises and this is the type of model that we are trying to encourage elsewhere. We are greeted by our host, the ebullient Frenchman Monsieur Gigi, who has managed to keep dinner warm for us.

Day 4, March 19: We head back to CSM for a meeting with a Madagascar National Parks (MNP) warden and staff to discuss improving enforcement and protection for the tortoise population here, arguably the densest and most important in all of Madagascar. The situation is challenging, compounded by the lack of a communications network in the area. Under the current system, MNP staff cannot arrest poachers and have to contact gendarmes that may be many miles away. Cell phones do not work in this area, and neither MNP staff nor gendarmes have access to vehicles. Villagers that want to report poachers from outside are frustrated by a lack of response from Forestry Department or the gendarmes, and usually by the time a response is made the poachers are gone. We determine that a radio network is urgently needed to allow improved communications and to speed the response time to poaching activity. MNP will develop a plan for where to station the radios for maximum coverage and we can then determine costs. Hopefully, this will allow us to “get ahead” of the impending threat that we know is coming from poachers. After lunch we drive to Marovato on market day to purchase the zebu for the upcoming festival. Due to ample rain and an exceptional growing season, the vendors feel no pressure to sell zebu and the price is too high so we decide to buy elsewhere.

Day 5, March 20: We spend the morning looking for tortoises at Cap St Marie down by the lighthouse. The vegetation is denser that I have ever seen it in this windswept landscape and there are ample hiding places for tortoises. Unlike my previous two visits, we find very few tortoises; the ones we find are tucked under clumps of low shrubs.

It feels very strange to not find tortoises at every turn, and of every age class. Last year at this time we managed to find more than 40 in a few hours of time, and with little effort. Herilala and Sylvain are also concerned by the apparent paucity of tortoises, but I hope that this is simply a reflection of hot temperatures, full sun and ample retreats.

In the afternoon we drive to the village of Antsakoamasy to discuss the upcoming festival and to see the zebu that we are buying for the occasion. The zebu is brought out, we approve, the price is agreed upon and a celebration ensues. The village erupts into displays of traditional dancing and singing in what is to be a prelude to the real festival five days later. With my receipt for one zebu in hand, this could likely the be first of many that I present for reimbursement, as zebu and rum celebrations are the standard means of formalizing an agreement with villages in the rural south.

Given the situation with rampant tortoise harvesting in this difficult to patrol and enforce environment, creating incentives for protecting tortoises at the community level will almost assuredly become an important strategy for us. Antsakoamasy was selected as a site for this pilot program because of the strong fady (taboo) that protects tortoises here, as it is believed the tortoises are the embodiment of their ancestors.

Day 6, March 21: We leave Lavonono early and drive due north for Beloha, another major tortoise eating center where we had documented a tortoise shell dump site and thriving meat market last year. We are here to pick up a confiscation of 14 radiated tortoises so we first visit the local Forestry officer Mosesy Valisoa who takes us to the local gendarmes facility. The tortoises – three adults and 11 juveniles – are being held in a jail cell but appear active and healthy.

Figuring out how to fit them in a Toyota Land Cruiser already packed with 6 people and a lot of gear is a challenge but we manage with plastic pans and rice sacks. We head off to the village of Ampotoka where we believe we will find an appropriate release site and people who are protective of tortoises.

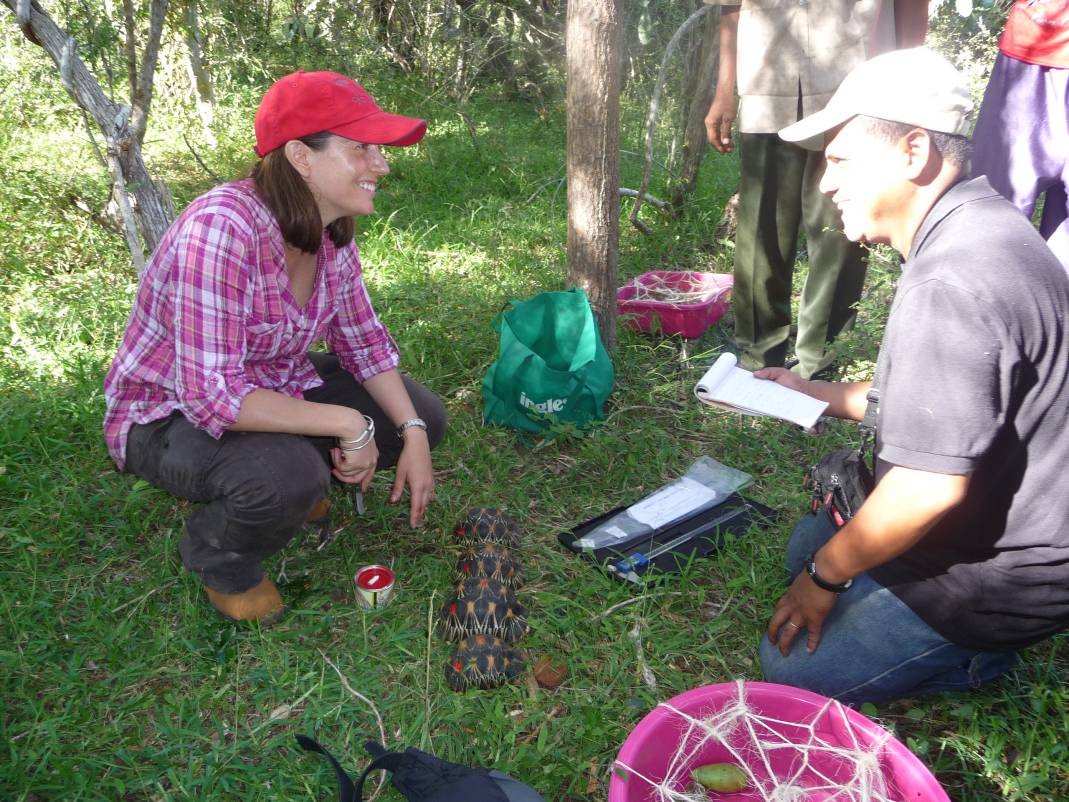

After arriving, we have a brief meeting with the village leaders and then head down to the Menarandra River to rehydrate the tortoises. Afterwards, we find a shady spot and build a corral for the tortoises and get them to eat Opuntia fruit.

We return to the village for a long meeting with the village about their history with tortoises. The tortoise population here is heavily depleted, the first wave of collection being in the 1960s when a pumping station was build nearly, then again in 2009 when a group of poachers came in for days and carried away many tortoises.

They are remote and unable to communicate with authorities, and refer to the situation across the river where the Mehafaly people are dealing with armed poachers and lives have been lost. However, they are committed to bringing tortoises back to their sacred forest and protecting them. We agree to buy a cell phone for the village so they don’t have to walk for days to report poaching violations to authorities in Beloha. We are welcomed by the village and while they prepare our dinner, Christina and Herilala process and mark all tortoises in preparation for release the next day. We then spend our first night camping in the field.

Day 7, March 22: With tortoises in hand, we are escorted into the sacred forest of Sirempo. The habitat is mildly degraded by zebu trails and Opuntia growth but has some good stands of intact spiny forest. We see numerous red stone burial tombs with ornate wood carvings characteristic of the Antandroy people. Surprisingly, we start to find tortoises and so begin releasing in areas where tortoises occur. In three hours, we locate seven wild tortoises, including a few large adults. We hope that these animals, in addition to the ones we release, will provide some basis for population recovery in this area.

The midday heat is intense and we return to village for a bit of rest. Later, we conclude our business with the village of Ampotoka and agree to help them to better communicate with local authorities and to support the release of future confiscations to help re-establish tortoises in their sacred forest. We spend our second night camping here.

Day 8, March 23: Today we head back to Beloha and meet with a local tortoise conservationist – a colorful and passionate individual that we refer to as The Rasta. He explains to us that tortoise consumption and selling goes unchecked here and local authorities - including some gendarmes - are tortoise eaters so enforcement is almost non-existent.

He guides us to numerous tortoise shell dump sites, disturbing evidence of the widespread practice of eating tortoise here. The recent tortoise confiscation is an exception, the result of a judge passing through who happened to witness the exchange of tortoises and arrested the poachers.

After lunch we head back to Lavanono and the Chez Gigi for my birthday celebration. While relaxing during the midday heat, we hear a commotion in the nearby village. Fishermen have caught a HUGE female green sea turtle and are intent on killing it for food. Herilala buys her for $25 and releases her in honor of my birthday. It was a very special moment with the village kids cheering and waving goodbye as she swam – head raised out of the water – back out to sea.

Day 9, March 24: Today is largely a day of rest, preparing for the big zebu celebration in Antsakoamasy. Herilala and Christina survey a few areas for tortoises but are soon driven in by the intense heat.

Day 10, March 25: We check out of Lavanono early and drive to Cap St Marie headquarters. We pick up the MNP warden in addition to tables, chairs, and a portable generator to power the sound system for the celebration. These are dropped off at Antsakoamasy then on to Maravato to pick up the mayor and other officials for the ceremony. The road is crowded with people walking to the festival site and we arrive to a lively and anticipatory crowd with loudspeakers already blaring music. We estimate that roughly 500 people are already there!

Visitors and guests are seated up front in a shaded area and the ceremony begins with Sylvain welcoming the crowd and explaining the reason for the celebration. We are here to recognize the village for their strong efforts to protect the Sokake (radiated tortoise) and to sign an agreement between the TSA and Antsakoamasy to build them a primary school. Herilala reads the terms of the agreement out loud to the crowd and then a huge banner is unfurled that will be used to seal the accord.

Over the next hour, selected villagers – including men, women and children - come forward and trace their hand print on the banner to signify their commitment to the agreement and Sokake protection. A series of speeches follow the hanging of the ceremonial banner, with a particularly rousing one by the Maravato mayor who extols the crowd to embrace Sokake protection as a means to a better future for their village.

We look around and realize that the size of the crowd has more than doubled to over 1,000 people, making it the largest crowd I have ever addressed! The zebu is sacrificed according to traditional practice, the rum starts to flow, and the dancing, singing and celebrating begins. We join in the traditional dancing as long as the heat will permit, then retire to the village president’s house to share zebu and rice.

The significance of the agreement between Antsakoamasy and TSA, and building the much needed school will hopefully be far-reaching. Word should travel fast and we hope that other villages will begin to understand the connection between protecting their local tortoise populations and seeing positive outcomes in their communities. We must be willing to provide incentives and reward tortoise protection locally, or else we will surely loose the battle to save the Sokake. This is a first step, but one that we believe can be catalytic throughout the region. Our challenge is to continue the process of identifying key tortoise populations that have nearby villages with a strong tradition of protection. This strategy, we believe, may hold the key to the survival of the radiated tortoise in the wild.

Day 11, March 26: After spending the night in Tsimombe we head out for the town of Antanimora, and arrive by lunchtime despite horrendous road conditions. We drive a few more hours and reach another village that is reported to provide good protection for their tortoises. We head off into their sacred forest which is now highly degraded habitat and if not for the village children, we would not have seen a tortoise. They locate two adults and everyone seems very surprised by the lack of tortoises. We return the next morning to search for tortoises and again find none. The village president appears truly bewildered by the lack of tortoises and suspects that they have not been monitoring their tortoises as well as they could. There are reports of poaching in the area and we suspect that this area may have been stealthily hit though this is unlikely; villagers are usually on guard against outsiders who may be stealing goats or zebu. In fact, the men of this village were distracted by a recent theft of goats. We camp here for the night and are entertained by traditional dancing and singing, in what became a full cultural immersion experience.

Day 12, March 27: We drive back to Ft. Dauphin for the night and catch a return flight back to Antananarivo (Tana) the next day.

Day 14, March 29: It’s a holiday in Madagascar so it’s good day to relax and enjoy some good French cooking in the restaurants of Tana.

Day 15, March 30: On our last day in Madagascar we have a day of meetings with the Missouri Botanic Garden and the World Wildlife Fund, settling finances and preparing for the long flight home.

Summary: The Radiated tortoise shares its range with four tribes – two that eat tortoises and two that do not. The Vezo tribe in the west and the Antanosy in the east have been eating tortoises for generations hence populations in the regions around Tulear and Ft. Dauphin are mostly cleaned out. In between are the Mehafaly and the Antandroy, the more numerous of the two. Together, their practice of fady (taboo to harm tortoises) is largely responsible for the fact that the radiated tortoise still survives today. If all four tribes in the south ate tortoises, they would almost certainly be gone.

However, tortoise consumption has increased dramatically in recent years and they are consumed now every day in some towns rather than just for special celebrations. This has resulted in a rapid reduction in population numbers, and the rate of decline is frightening, unsustainable, and the reason that the species was elevated to Critically Endangered status in 2009.

With Vezo poachers invading from the west and the Antanosy coming in from the west, the strength of the protective fady is being put to the test. In some villages it is very strong and they will go out of their way to confront poachers, believing that the tortoises harbor their ancestors’ spirits. In other villages the fady may be weak and benign, and though they may not eat or harm tortoises, they do not mind if others come in to take them. This is why we must create a strong connection between having tortoises in your village with an improved community. Antsakoamasy is the example that we hope will carry this idea forward.

Our primary challenge is to identify healthy populations of tortoises that are in close proximity to villages that practice a strong protective fady, and then work with those communities to provide incentive for protecting tortoises. However, this could be fraught with challenges as well because - increasingly - poachers are growing bolder and more aggressive. There are reports of bands of tortoise collectors being dropped off in an area for two weeks and efficiently cleaning out the forests. Both adults and juveniles are often taken, leaving little potential for population recovery.

The radiated tortoise may be on its last legs, but the battle to save them is not over yet, and we (TSA, The Orianne Society, Nautilus Ecology, Henry Doorly Zoo’s Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership) are approaching this challenge with a renewed sense of vigor. The period of disbelief following last ye